March 12, 2024

Author

The Shifting Landscape of Natural Resource Economics at ECOnorthwest

The firm’s oldest practice, natural resources, grew out of its original insight: the second paycheck.

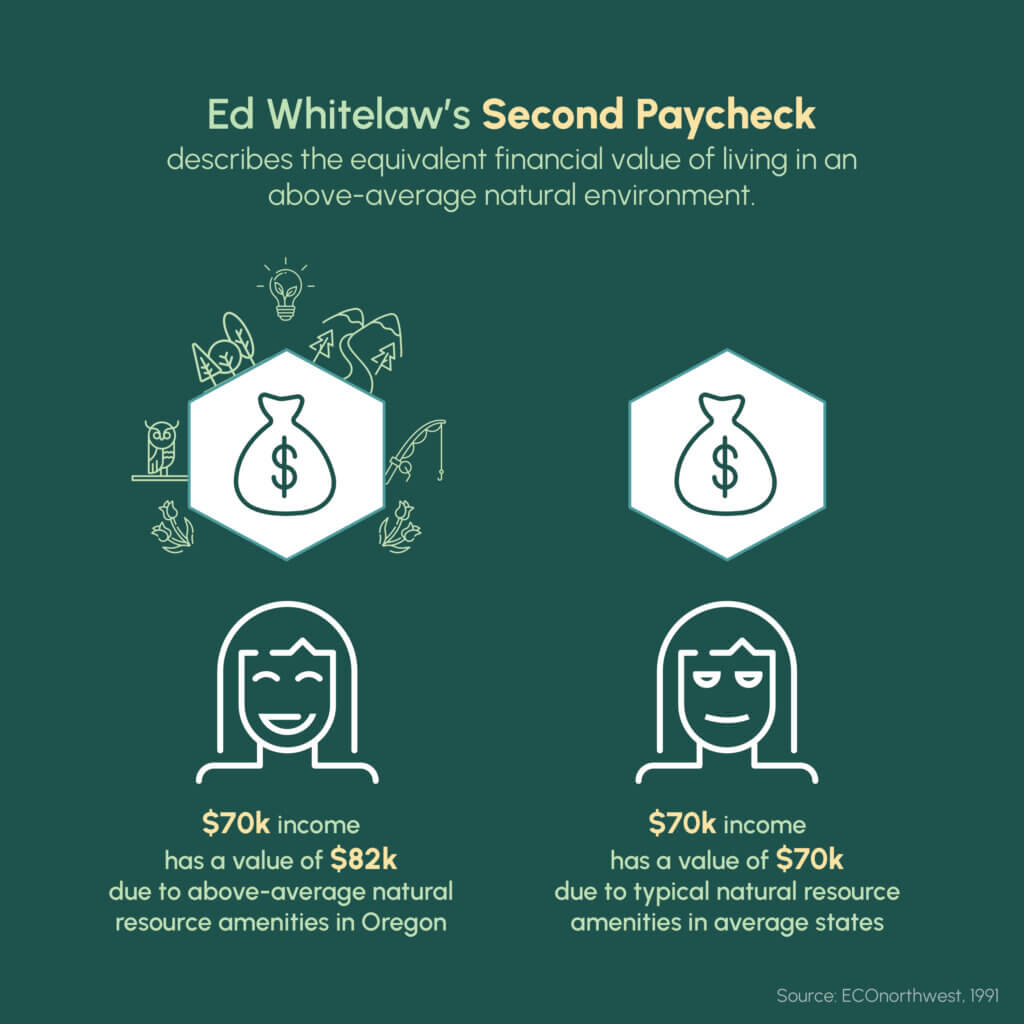

The second paycheck theory asserted that workers in the Pacific Northwest were paid twice—once by their employer and once by the stunning natural settings they enjoyed. The evidence was on our side. In the 1970s, Americans were increasingly migrating to places they wanted the jobs to be—not necessarily where the jobs were—and they were giving up some of their wages in exchange for beaches, rivers, vistas, and clean air. “An attractive environment was money in the bank,” said our founder.

Ed Whitelaw’s Second Paycheck describes the equivalent financial value of living in an above-average natural environment.

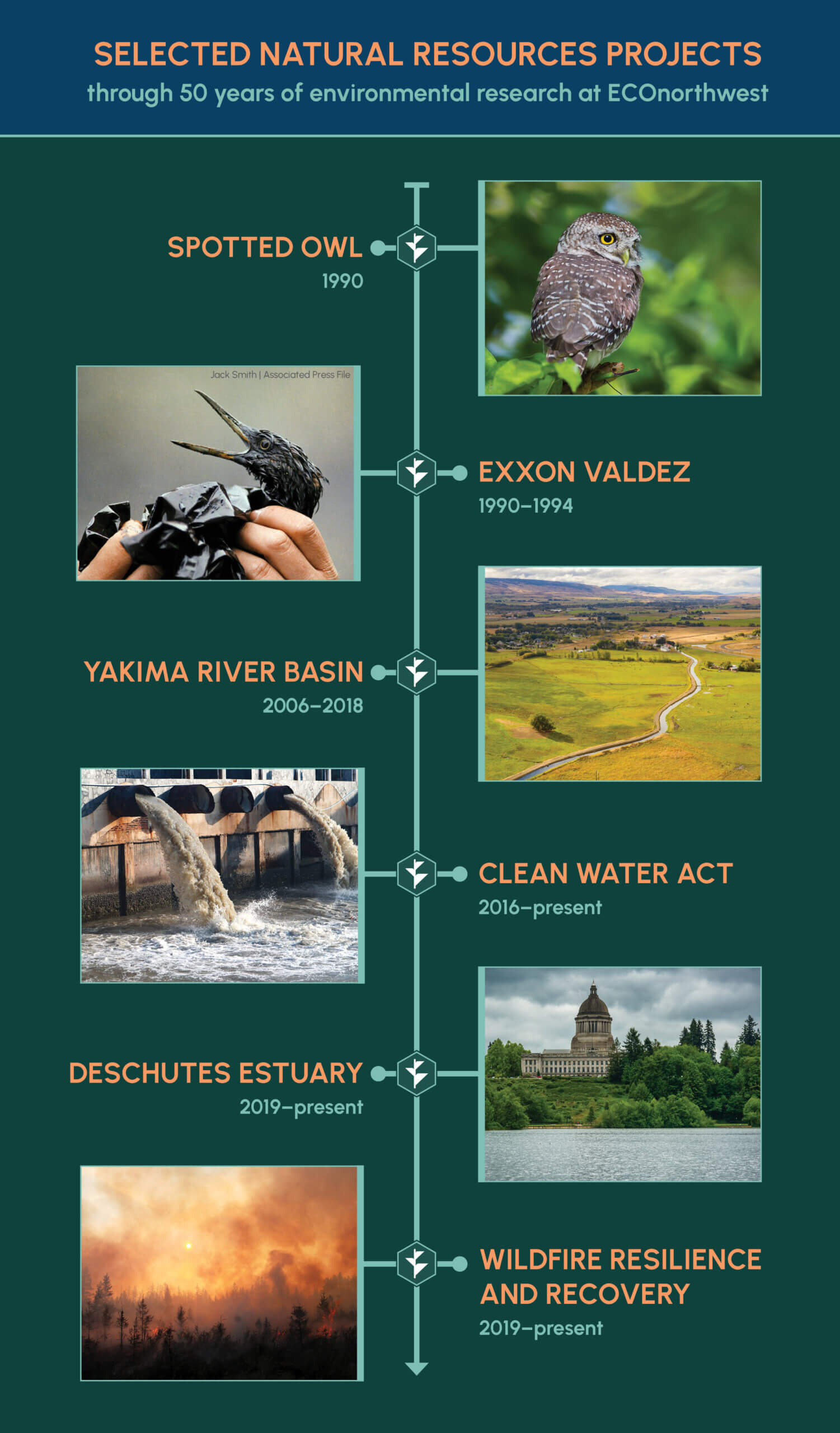

The second paycheck theory, which made the economic case for thoughtful resource management, was highly controversial in a region that had long relied on timber and fisheries for its economic vitality. ECO anticipated an inevitable shift from legacy resource-based industries to a knowledge-based economy. That transition was accelerated by the listing of the Northern Spotted Owl as an endangered species and associated logging restrictions on federal land.

“The sky did not fall” in the aftermath of the restrictions, we declared in a widely distributed 1999 report. And thanks to growing technology sectors in Portland and Seattle, we were right if measured at a broad regional level. But within the region, a wide urban-rural economic gap opened. The sky did fall on many isolated, timber-dependent communities.

Our work has evolved in two important ways since those early, divisive days.

First, our clients, and we, have focused more on community engagement and the distributional effects of natural resource policies. Where are the benefits enjoyed and the costs borne? And precisely by whom? No one wants to relive the trauma of the timber wars: crushing rural costs and diffuse benefits enjoyed in faraway urban centers. Moral and economic imperatives demand that costs and benefits be shared more equitably than in the past.

Second, we’ve improved our understanding of the value of a thriving environment. Well-managed natural areas purify water and air, moderate temperatures, control floods, limit pests, foster biodiversity, create recreational opportunities, inspire cultural traditions, and more. These “ecosystem services” went from the fringe of policy analysis to the center during our 50 years of consulting.

Deep community engagement and a comprehensive understanding of ecosystem services came together in our 2006–2018 work in the Yakima River Basin (YRB)—a landmark study to inform a 30-year water management plan. Few regional economies in the nation rely on water more (40 percent of the basin’s jobs are water dependent compared with 16 percent nationally), and long-range forecasts predict droughts and water scarcity. Competing users in many similarly situated regions choose litigation, but YRB’s users opted for collaboration and investment. ECO found the investment plan—a mix of reservoir enhancements, dam removals, new fish passages, forest conservation, and more—would boost fish harvests, prevent crop losses during drought years, lower water rates, and create 27,000 jobs. It’s a model for the increasingly thirsty West.

Deep community engagement and a comprehensive understanding of ecosystem services came together in our 2006–2018 work in the Yakima River Basin (YRB)—a landmark study to inform a 30-year water management plan. Few regional economies in the nation rely on water more (40 percent of the basin’s jobs are water dependent compared with 16 percent nationally), and long-range forecasts predict droughts and water scarcity. Competing users in many similarly situated regions choose litigation, but YRB’s users opted for collaboration and investment. ECO found the investment plan—a mix of reservoir enhancements, dam removals, new fish passages, forest conservation, and more—would boost fish harvests, prevent crop losses during drought years, lower water rates, and create 27,000 jobs. It’s a model for the increasingly thirsty West.

We brought our same toolkit to a stalled debate over the restoration of the Deschutes Estuary in Olympia. There, the 1950s-era dam that created Capitol Lake as a reflecting pool for the State Capitol campus had disrupted tidal flows and near-shore ecosystems critical for sustaining salmon. Sediment accumulated, aquatic weeds bloomed, invasive species proliferated, and water quality deteriorated, closing the waterbody to all public access for over a decade. ECO’s recent work highlighted a range of benefits of restoration—from supporting economic development in downtown Olympia, to sustaining cultural value to the Squaxin Island Tribe—and identified how the state and local jurisdictions could pay for it. The findings helped the region break through decades of inaction and build a collaborative foundation for the state-led partnership to begin planning for dam removal and estuary restoration. ECO’s work continues as we help the state implement a diverse funding strategy that will ensure the project’s benefits are realized over the next decade.

Much of our work takes place in the community, but some of it takes place in court. In enforcing the Clean Water Act, governments have long relied on a rigid schedule—a fixed penalty amount for every day a firm is in violation. Our take: rather than issue the conventional post-violation fine, why not discourage the bad behavior before it starts? It’s a century-old idea credited to Arthur Pigou. Attorneys for federal justice and natural resource agencies have turned to ECO’s experts to develop a new framework for penalties that takes into account the public costs as well as the benefits to violators to improve deterrence, scaled appropriately for both large chemical corporations and small private businesses to avoid putting them out of business.

Our recent work isn’t all about water. Our growing wildfire qualifications are an unfortunate sign of the times. ECO has quantified the damages of New Mexico’s Calf Canyon/Hermit Creek Fire to help localities apply for federal emergency aid, identified post-fire economic opportunities in Oregon’s Santiam Canyon, and testified on the certification-of-class-action lawsuit against Pacific Power for their role in Oregon’s 2020 Labor Day fires. It’s the kind of work that everyone at ECOnorthwest hopes we see less of.